Astronomers had been keeping records in early Babylonia since the

19th century Before the Common Era, (History of Babylon), and the Chinese have been keeping records of the

stars since at least 3000 BCE, and probably for a lot longer than that. (Ancient Chinese Astronomy) And though

we may not have intact records from other ancient cultures, we can be fairly certain they weren’t ignoring the stars,

either. And they all concluded the same thing: The earth is in the center of the Universe. And why not?

After all, if you watch the stars for very long at all, that’s exactly what they do – they go in circles around

the earth, and so does the moon and the sun... more or less. It’s the planets that are... a bit more problematic.

All these things circling the earth even got more confusing when early astronomers and philosophers began

questioning just exactly how that all worked. Enter Plato who came on the scene around four hundred years before the

birth of Christ. (Plato)

Plato, seemingly determined to make things more confusing than they already were, felt “...that the

world was constructed with geometric simplicity and elegance....” He believed that the circle was the simplest

form of uniform motion, and if something were going to repeat itself endlessly, which the universe seemed to be doing, then

the best way to do it had to be a circle – a perfect circle. (Fowler)

But

there were just two small problems with that idea. One, the earth, as those of us who didn’t attend public school

in Texas, Kansas, or Mississippi know, is not in the center of the universe, and two, nothing in space

goes in a perfect circle, much less the planets’ orbits of the sun. And that’s were epicycles come in.

Early astronomers knew that the planets were not the same as stars from just about forever. The planets

move faster than the stars around them, they are often brighter, and they do this funky thing called retrograde motion.

That’s when we pass a planet in orbit, or that planet passes us. It happens more often than one might think.

What the planet appears to do when that happens, over the course of several evenings, is to slow down, stop, then go the opposite

direction before slowing down, stopping once again, and then going back in the direction it was originally heading.

(Strobel) Think about passing another car on the highway, but you don’t realize you’re moving, too.

That sort of thing would mess with even the best models, much less a model where the only path possible

was a perfect circle, and a model of the Universe is exactly what Plato challenged his colleagues to make, which is a lot

easier than doing it yourself. And they did!

Of course, they also came up

with some pretty crazy stuff as well, such as was envisioned by Eratosthenes and Aristarchus around the 3rd Century

BCE, (Size of the Earth...) who came up with the idea that it was the sun that stayed put and that the earth, while

rotating on its axis once every 24 hours, went around the sun. (Fowler) Now who’s going to believe that?

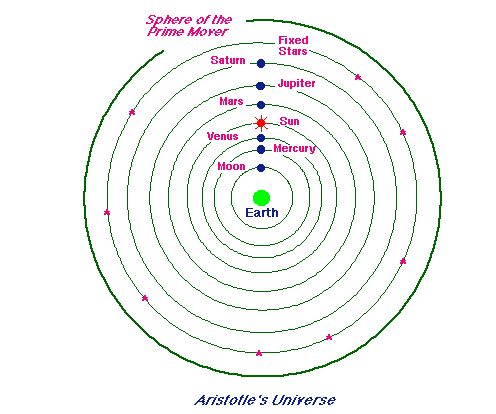

Though Plato first came up with the idea of an epicycle, it was Ptolemy in the 2nd Century

CE who perfected the epicycle, building on the earlier work of others, most notably Hipparchus, who developed trigonometry

just to figure all this out. By having a planet orbiting a point on a circle that orbits the point on another circle,

which, if necessary, could be orbiting a point on even another circle, and so on, Ptolemy came up with an ingenious model

of the solar system (and ostensibly, the Universe) – and the geometry to back it – that actually worked.

He was able to prove, mathematically, that the earth was, indeed, at the center of the Universe. And all of these circles

on top of circles were called epicycles. (Fowler)

Epicycles (Fowler)

And then along came the Catholic church, and not long after that, syncretism: The blending

of pagan and Christian traditions. In a pea pod, it was the attempt of early Christian theologians (among others) to

make everything that clearly had nothing to do with Christianity a part of the Christian tradition. (Botkin) To

these theologians, it made perfect sense that if we are God’s primary creation, then we should be smack dab in the center

of everything. And, if God is going to make something, then it wouldn’t be anything less than perfect. And

nothing was more perfect than a circle.

And so Ptolemy’s model of the universe

with all of its epicycles became part of the dogma of the Catholic church. In other words, it became the word of God

that the earth was in the center of the Universe. (The History of Dogmatic Thought) And there it stayed until

1543, when Copernicus published The Revolution of the Celestial Spheres, in which he suggested that it was the

sun that stayed put and the earth that did the loop-to-loops. (Wudka) Copernicus was wise enough, though, not

to directly challenge the Catholic Church, but instead presented his ideas as just a theoretical way of understanding the

universe. Galileo, on the other hand, believed he could convince the church that it was wrong. After all, the

Pope was one of his buddies, and it had been over a century since Copernicus had publically introduced the idea. That

friendship (though a bit strained) was probably the only thing that kept Galileo from being killed for heresy, that, and he

renounced his theories, more or less. (Loy)

But the dogma had been let out of the

kennel, so to speak. The world was clearly round, as attested to by Columbus and other early explorers, and everybody

who tested Galileo’s theories with his newly improved telescope could clearly see that he was correct. The world

could no longer return to believing it was in the center of the Universe. Of course, the Catholic Church was a bit slower,

not removing Galileo’s book, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World

Systems, from their index of banned books until 1835, and not officially admitting that they were wrong until 1979.

(Loy)

To me, Epicycles have come to represent how easy it is to prove that something is true when

you believe it already is before, or even if, you ever go looking for proof. As well, they represent how hard it is

to change those beliefs which are clearly not right, especially when those beliefs have gotten entangled with religion. Epicycles

are nothing more than a clockwork orange – a beautiful mechanism that does nothing. (Burgess) But yet they

remain.